The interpretation of dreams is a subject that has fascinated scholars across time and provided inspiration for countless works of literature. Dante Alighieri’s eminent The Divine Comedy begins with its narrator ‘so full of sleep’ that he finds himself lost in a ‘great forest’, whilst Cicero ends his De Republica, a dialogue so rooted in the complex, rational politics of the Roman Republic, with a Platonic dream vision promising a grand future empire for Publius Scipio, if he can find the courage and virtue to foster it.[1] Macrobius was considering the latter text when he produced his five categories of dream interpretation, two of which, the oraculum and the visio, proposed that some dreams possess a prophetic power that can inform the subject of a potential path to betterment, or disaster. Therefore, it is only natural that writers of fictional dream visions would use the genre to propose futures that they believed ideal; Cicero’s De Republica, after all, was written with the intention of spreading his ‘idealised picture of the Roman constitution and of Roman law’ to the general public, and its final book was no exception.[2] As Phillips writes, the dream vision genre is unique in that it can allow ‘for satire or amusing and amorous subjects’, but also ‘serious purpose and enlightenment’.[3] It provides a space not only to stretch the imagination, but also for the poet to provide genuine social commentary, and proposals for where humanity could yet head.

Unreliable Narrators

One of the main tenants of the dream vison poem is the unique disposition of its narrator. They are described by Phillips as often ‘half representative of the author, half character’, and in the works of Chaucer, tend to be ‘spectators rather than protagonists’.[4] More specifically, they tend to be spectators with no prior knowledge of what it is they are going to see, and very little insight whilst they are seeing it; often this is due to them bearing witness to ‘a panorama that overwhelms the senses and cannot possibly be given an adequate description’, leaving them ‘puzzled, inadequate’ and ‘unassertive’.[5] Again, this is common to Chaucer’s dream poetry, such as in The Book of the Duchess whose sleep-deprived narrator admits he take ‘no kepe/Of noothinge’, or in the case of The Parliament of Fowls, where Love so ‘Astonyeth’ the narrator that he claims ‘Nat wote I wel wher that I flete or synke’.[6] Nowhere, however, is this more the case than in The House of Fame, whose dreamer is so ‘hapless’ that Smith denounces him as a ‘clearly inferior narrator’ for the tale.[7] Like the ‘Light of heart’ narrator in The Romance of the Rose, who does ‘gaze with pleasure’ at the paintings adorning the walls of The Garden of Pleasure, Geffrey bears witness to the ‘ryche tabernacles’ and ‘curiouse portreytures’ in the temple of glass.[8] But unlike the Romance, there is no Lady Idleness to explain these sights, and the narrator remains clueless as to their true meaning. Indeed, the numerosity of this ekphrasis serves to translate the overwhelming confusion felt by Geffrey onto the reader, a sense of bafflement not helped by what Smith calls a ‘self-aware series of wilfully poor lines’.[9] Chaucer intentionally characterises Geffrey as lacking in poetic skill, as he often admits that ‘nyste I never, redely’ what he sees, and even attempts to dodge the burden of comprehensive description with such evasive manoeuvres as ‘What shuld I make lenger tale/Of alle the peple y ther say,/Fro hennes unto domes day’. It is peculiar, then, as to why Geffrey is also described as being constantly sat ‘at another booke’ by the Eagle, and as often trying to ‘set thy witte […] To make bokes, songes or ditees’. The golden bird even calls his dialect that of a ‘lewde man’ later on (HoF, 363, 356, 358). The characterisation of Geffrey as a poet who is bookish, yet also lacking in true artistic appreciation or inspiration, is pertinent to Chaucer’s wider, societal aim with The House of Fame, for its narrator represents those who are so complacent with the familiarity of the existing literary tradition, that they consider not to pursue the experience that could exist outside of it; they sit at their desks, alone, ‘domb as any stoon’ (HoF, 356).

The failings of Geffrey’s narration lead to a sense of unreliability in what he tells, as he often falls short in accurately depicting that which he sees. A similar impression is cast over the narrator of William Langland’s Piers Plowman, as Langland strives to embody in Will the shortcomings he perceives in his own society. From the prologue, as Will looks out upon ‘A fair feeld ful of folk’ overlooked by Truth’s ‘tour’ and blemished by False’s ‘dongeon’, he sees ‘alle manere of men, the meene and the riche’ going about their lives.[10] However, within the masses he envisages those whom ‘In countenaunce of clothynge comen disgised’ in order to cheat their way into ‘heveneriche blisse’: beggers who ‘Faiteden for hire foode’, the pilgrims who ‘leve to lyen’ with their ‘many wise tales’, friars who ‘Glosed to gospel as hem good liked’, and a ‘pardoner’ who ‘preched […] as he a preest were’ (PP, 2-3). All of these wrongdoings are grounded in trickery and deceit, a fact that becomes even more pressing once Will himself is taken into account, who is introduced as being dressed ‘into shroudes as I a sheep were’ (PP, 1). Galloway writes how this implies ‘self-concealment as well as self-presentation’, a theme of hollow insincerity that plagues Will constantly, such as in the beginning of Passus XIX:[11] he says he ‘dighte me derely, and dide me to chirche’ in a show of outward piety, only to fall asleep midway through the congregation (PP, 235). It is this element of false religious affectation that Langland finds particularly troubling. After all, as Reason tells the clergy in Passus V, ‘That ye prechen to the people, preve it yourselve’ (PP, 43), and Schmidt goes on to write that ‘the clergy […] are the root cause of the good as well as the evil in the whole community. Their holiness makes it holy, their viciousness makes it vicious, because lay-people understand their teaching through their example’.[12] For Langland, Simpson writes, ‘the sacrament of penance […] is crucial, since it allows Christians [to pay back] their spiritual debts’ to Christ; when the ‘material need of the mendicant friars prompts them to sell the sacrifice of penance short […] then the friars are destroying the church by transforming the sacrament of penance into a business’.[13] Indeed, it is the friars that Langland views as being at the centre of the decline of the institution of the Church. It is they who give Liar sanctuary from the King in Passus II, so he can ‘hath leve to lepen out as ofte as hym liketh’; it is they who ‘folwede that fend’ Antichrist in his assault on the Barn of Unity in Passus XX; and it is ‘Frere Flatere’ who ultimately allows, by means of the same sanctimonious deceit that Langland condemns so many times before, ‘Sire Penetrans-domos’ into the Church to destroy it from the inside (PP, 23, 253, 262). When Contrition fails to cry at confession, it is because the friars have turned the sacraments from an emotional obligation, into a financial transaction.

Dreaming of a Better Tomorrow

It may seem, then, that Langland’s is a text aimed for revolution against the rotting institution of the Church. When he has clergy ignore Conscience’s plea for help in Passus XX, who is described in Schmidt’s explanatory notes as a knight with ‘the power to make (moral) decisions in the light of God’s law’,[14] it seems he is completely sundering religious institution from the pursuit of Truth. However, Simpson argues that this is not the case. Whilst it is true that Langland believes that ‘only Conscience, is capable of a truly reforming impulse’, a ‘Conscience produced by a failing church is incapable of reforming that church’. For the poet, ‘The church as an institution is an inherent part of the story of the soul’s education’.[15] The reason that Piers Plowman proved so popular in such violent revolutions as the Peasant’s Revolt of 1381, when John Bull urged the men of Essex to ‘stand together in God’s name, and bid Piers Ploughman go to his work’,[16] was because of the doctrines that Langland wanted to reform the Church around, far simpler than those which the ecclesiastical order preached. In Simpson’s words, Langland’s ‘sense of history’ is ‘consistently a sense of decline from pristine beginnings’; in Passus XV, Anima, representing the unified human soul, ‘critiques the contemporary institution of the church by broad comparisons with its historical beginnings’, locating ‘the ideal of charity […] in the past’ since marred by the material necessities of the medicants.[17]

No more explicitly is this desire articulated than in the allegorical tearing of the pardon in Passus VII, where the path to Truth is revealed to be infuriatingly simple. It is written in Latin, which in the Prologue was shown to be the language spoken by the angels, but still the priest dismisses it as ‘no [real] pardon’ and mocks Piers’ status as a layman when he goes to read it. Enraged, Piers rips the pardon in two; but this is not a rejection of its message, as Piers subsequently declares that ‘Of prieres and of penaunce [his] plough shal ben herafter’ (PP, 83). Instead, the act could be seen as a rebellion against the attempt to bind words of Truth within human documentation (many laymen at the time would have relished doing the same to the Statute of Labourers). Rather than loud academic pursuit, which Langland viewed as causing the clergy to ‘lose the motivation of their founders […] further growth in holiness’, Schmidt writes of Langland’s conviction that ‘man’s task is to imitate Christ in trusting God’.[18] Thus, Piers Plowman stands on the ‘side of literal poverty and the simplicity of life as the antidotes to greed, envy and pride’.[19] Upon accepting the pardon, Piers disappears, returning in the Vita as the guardian of the Tree of Charity, then in the countenance of Christ, and finally as St Peter, where he founds the Barn of Unity. Rather than the Church being cast aside by Langland, its founding is the ultimate, integral outcome of Piers’ spiritual transformation, due to his accepting the most basic of truths above all else; as Holy Church tells Will far back in Passus I, ‘Whan alle tresors arn tried […] Treuthe is the beste’ (PP, 12). The first thing that the Antichrist does upon his appearance is ‘al the crop of truthe/Torned it […] up-so-doun’ (PP, 253); he is trying to uproot the people from their foundations in the values of Truth. Finally, when Conscience embarks on a pilgrimage from the ruins of the Barn of Unity to find Piers, he is embarking on the same cycle once more, to find the divine simplicity amidst infernal chaos.

The House of Fame, while not so reliant on personification allegories, has a handful of spiritual, didactic characters, one of whom is the golden Eagle. While the bird does chastise Geffrey for his prioritising study over worldview, he also brings tidings of better fortune, informing Geffrey that he has been sent by Jupiter to bring him up to the House of Fame, where he will find ‘tydynges/Of Loves folk […] So that thou wolt be of good chere’. After all, the ‘queynte maner of figures’ in the temple of glass brought Geffrey more bewilderment than joy (HoF, 356 and 350). As such, Chaucer’s poem also contains a cycle from complexity to simplicity, this time depicting the process of forming one literary tradition from another. Geffrey’s journey through the world of The House of Fame is built around a number of intertextual allusions and inversions. As Christopher Smith writes, ‘the eagle that abducts Geffrey’ can be interpreted as ‘a humorous combination of the appearance of Virgil and the device of assent’ in Dante’s Divine Comedy, yet this particular supposed didactic journey ‘leaves us with more questions than answers’.[20] The meeting with the eagle is very reminiscent of Philosophy’s introduction to Boethius; Geffrey mistakenly thinks that he is being ‘y bore up as men rede,/To hevene with daun Jupiter’ (HoF, 355), similar to how Boethius admits to Philosophy that he coveted the almost celestial heights of the ‘safety of the Senate’, and like how Boethius’ recognition of Philosophy as the ‘nurse in whose house [he] had been cared for since [his] youth’ begins their dialogue properly, the Eagle speaks ‘Ryght in the same vois and stevene/That useth oon I koude nevene’ (HoF, 355)(with Phillips unpicking the wry subversion here, in how there are suggestions that ‘this person might be Chaucer’s wife or servant’ impatiently rousing him, instead of a graceful, divine intervener).[21] Moreover, Geffrey is rebuked by the Eagle for his inability to conceptualise the universal plane through human interpretations; ‘Wilt thou lere of sternes aught?’ (HoF, 360); in a far less noble parody of how Africanus asks Publius ‘”Tell me, how long will your thoughts be fixed down on the ground?”’.[22]

With this in mind, it is clear that the characterisation of Fame’s judgement as arbitrary in The House of Fame’s Book 3 feeds into an idea that the embellished retellings of narratives in the literary canon are not always precisely as they occur in real life, or at least, what Geffrey perceives in his mind as reality. The beryl, magnifying walls of Fame’s House that ‘made wel more than hit was/To semen every thing’ (HoF, 1290), exaggerating the unimaginable treasures adorning its chambers, seem parallel to the false promises of the female personification of Fortune that Philosophy warns Boethius about, saying that ‘with her display of specious riches good fortune enslaves the minds of those who enjoy her’, until she reveals her ‘capricious, wayward and ever inconstant’ true nature,[23] and instructs Aeolus to blow his ‘blake trumpe of bras,/That fouler than the devel was’ at even the most righteous of men (HoF, 367). Similarly, Coley writes that the medieval stained glass was designed so that it ‘illuminated— architecturally and spiritually— the space into which they were integrated’;[24] thus, the works arbitrarily chosen by Fame to be exalted in Venus’s temple are embellished by its glass walls until it would be difficult to imagine anything beautiful beyond their splendour. But beyond their splendour Geffrey does travel, out into the vast, formless desert surrounding the temple, as Moses led the Israelites from the existing structure of the Pharoah’s tyrannical reign and into the perils and promises of a new life beyond Sinai. It is no coincidence that the Eagle speaks of ‘moo tydynges […] moo loves newe begonne […] Mo murmures and novelries’ to be found ‘then greynes be of sondes’ (HoF, 356); the same sand that surrounds Geffrey in the desert the raw material to form the glass of a new temple. Similarly, the reason that the House of Rumour is ‘mad of twigs’ (HoF, 370) is that wood is the raw material for a carpenter to create new structures, one such carpenter being the lowly workman whose words founded one of the largest religions on Earth. Likewise, within the House of Rumour are the raw, unprocessed ‘tydynges’ of all humanity, yet to be siphoned out by Fame; it is this unfiltered wealth of experience that can be used by Chaucer to form a new literary tradition from the English vernacular, that will stand next to the existing glass temples of old.

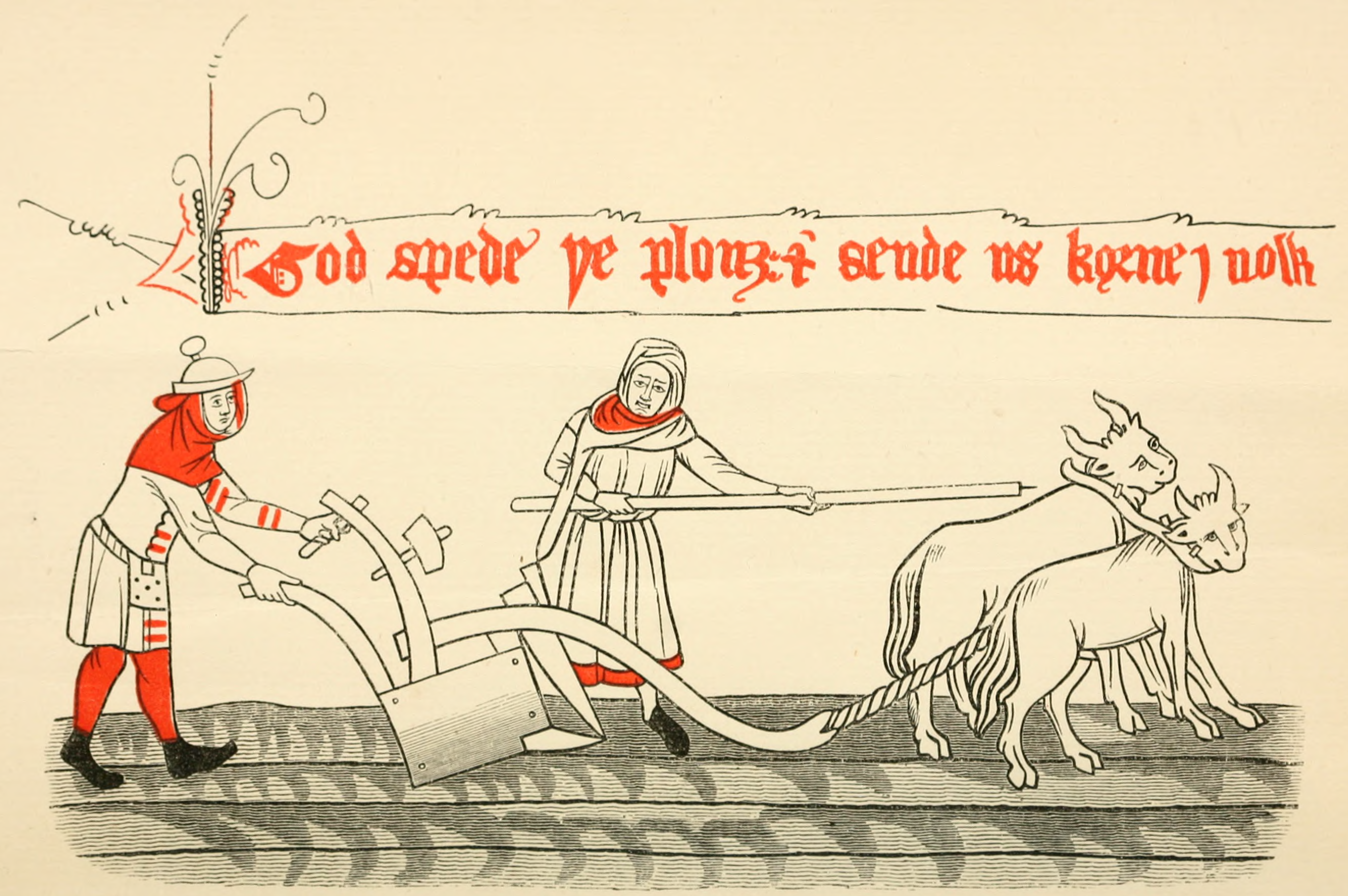

Thus, as Macrobius postulated that some dreams harboured prophetic elements, both The House of Fame and Piers Plowman offer prospects of future society that their poets view as ideal. They speak of cyclical processes, that take complex, pre-existing structures and seek to revitalise them by returning to simpler roots. For Langland, it is precisely the convolutions and hypocrisies of his society that allowed sin to fester; in Schmidt’s words, ‘spiritual evil (sin) threatens to drain meaning from creation, producing a ‘darkness’ in which nothing can signify, because nothing can be distinguished’.[25] In The House of Fame, Chaucer portrays the importance of moving beyond the fixed literary tradition and broadening your perspective with worldly experience; as Philosophy tells Boethius, ‘That is the place where I once stored away— not my books, but— the thing that makes them have any value, the philosophy they contain’.[26] Thus, both portray the necessary cycles of reversal that society must tread, both back to the root of spiritual philosophies and artistic canons, to recentre its aim going forward away from corruption. After all, for a ploughman to yield a new crop, he must first turn over his field.

Bibliography

Alighieri, Dante, The Divine Comedy, trans. Sisson (Oxford: OUP, 1998).

Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, trans. Watts (Penguin, 1999).

Coley, David, ‘“Withyn a temple ymad of glas”: Glazing, Glossing, and Patronage in Chaucer’s House of Fame’, The Chaucer Review, 45:1 (2010).

Cicero: Laelius, On Friendship & The Dream of Scipio, ed. Powell (Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips, 1990)

Chaucer’s Dream Poetry, ed. Phillips and Havely (Essex: Longman, 1997).

Galloway, Andrew, The Penn Commentary on Piers Plowman, Vol 1, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press).

Langland, William, Piers Plowman, ed. Schmidt (Oxford: OUP, 2009).

Langland, William, The Vision of Piers Plowman, ed. Schmidt (Everyman’s Library, 1991).

The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Benson (Oxford: OUP, 2008).

The Romance of the Rose, trans. Horgan (Oxford: OUP, 1999).

Simpson, James, Piers Plowman: An Introduction, 2nd edition (Liverpool: LUP).

[1] Dante Alighieri, The Divine Comedy, trans. Sisson (Oxford: OUP, 1998), p.47.

[2] Cicero: Laelius, On Friendship & The Dream of Scipio, ed. Powell (Wiltshire: Aris & Phillips, 1990), p.121.

[3] Chaucer’s Dream Poetry, ed. Phillips and Havely (Essex: Longman, 1997), p.3.

[4] Ibid, p.12.

[5] Ibid, p.2.

[6] Ibid, p.50.; Ibid, p.233.

[7] Christoper Smith, ‘Under the Reign of Doubt: Chaucer’s House of Fame and Narrative Authority’, ed. Pettit (2003) https://concept.journals.villanova.edu/article/view/141/112 (visited 17/05/2022).

[8] The Romance of the Rose, trans. Horgan (Oxford: OUP, 1999), p.4.; The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Benson (Oxford: OUP, 2008), ed.3, p.350 (hereby parenthesised in essay as (HoF, p)).

[9] Smith, p2.

[10] William Langland, The Vision of Piers Plowman, ed. Schmidt (Everyman’s Library, 1991), p.1 (hereby parenthesised as (PP, p)).

[11] Andrew Galloway, The Penn Commentary on Piers Plowman, Vol 1, (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press), p.2.

[12] William Langland, Piers Plowman, ed. Schmidt (Oxford: OUP, 2009), p.xxii.

[13] James Simpson, Piers Plowman: An Introduction, 2nd edition (Liverpool: LUP), p.109.

[14] Schmidt, p.265.

[15] Simpson, pp.105-106.

[16] Schmidt, p.xii.

[17] Simpson, p.103.

[18] Schmidt, p.xxii-xxiii, p.xxv.

[19] Schmidt, p.xxv.

[20] Smith, p.3.

[21] Boethius, The Consolation of Philosophy, trans. Watts (Penguin, 1999), p.11, p.7; Phillips, p.148.

[22] Cicero, p.141.

[23] Boethius, p.44.

[24] David Coley, ‘“Withyn a temple ymad of glas”: Glazing, Glossing, and Patronage in Chaucer’s House of Fame’, The Chaucer Review, 45:1 (2010), p.62.

[25] Schmidt, p.xl.

[26] Boethius, p.17.