Hello readers,

I was once sat in a hotel room with my girlfriend, flicking through the available TV channels in the usual apathetic manner, when a program on David Hockney caught my eye. For those uninitiated, Hockney is a well-respected British artist whose colourful and uncomplicated style makes him an accessible addition to curriculums in schools around the country (including my own). Born in 1937, he’s been a long-lasting institution in British art, and I have always enjoyed his vivid and varied portrayals of the British countryside. He himself is also a likeably irreverent character, wholly unbothered by his own immense success.

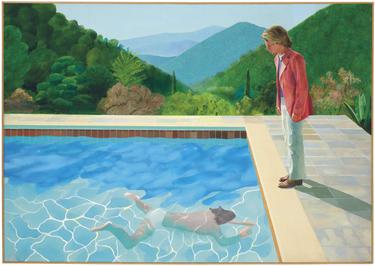

(As a contemporary sidenote— his ‘Portrait of an Artist’ happens to be the inspiration behind a notable painting in the genius and bizarre Netflix series ‘Bojack Horseman’.)

This scribbling, however, is not about David Hockney’s art. Instead, it is about something that he said during the interview I was watching.

See, Hockney’s uncluttered, minimalist style is as much about the areas of emptiness as the moments of life and colour. His landscapes are often static, conspicuously absent of any human being. There is a simplicity to the plain, untouched scenery that he depicts, but they also possess the agonised weight of expectation, like a stage backdrop moments before the arrival of the actors. One gets the sense that something is about to fill the silence, and yet the perpetuity of the moment captured before the noise is far more evocative than the noise would be itself.

When pressed about this, David Hockney said something that has lasted with me many months later— “Space is where God exists”.

Far from being some Augustinian mantra about the divine existing outside of space and time, Hockney was of course speaking to the importance of appreciating when a brush stroke is not needed, as much as when it is. However, this being a predominantly literary blog, I’d like to take a moment to apply this philosophy to the practise of effective writing. That is, regarding the blank space between the words on the page, that which the author does not explicitly describe, and, most importantly, that which the reader is left to imagine for themselves.

One of the points ubiquitous across creative writing lessons is the observation of avoiding long, laborious and aimless character description. In such a misled instance, each physical feature of a character, from the colour of their eyes to the length of their hair to the knock of their knees would be laid out in detail, until the reader’s gaze glazes over at the wealth of entirely arbitrary imagery. This is a classic instance of the writer aggressively inserting their own authority into the experience of their work, and doesn’t allow the reader to conjure their own personal conception of the character. After all, in being allowed to freely picture a character, the reader is subtly tailoring their perception along lines that fit their own experiences, meaning that the author’s conception of their own character likely (and rightly) won’t match the reader’s.

This can be clearly seen in the inevitable frustration that comes from screen adaptations of novels, where the actors chosen to play certain parts will never satisfy the expectations of every fan of the source material. And yet, if a writer provides so much concrete detail that it becomes suffocating, the reader will not be able to personally identify with their own imagining of the character— it will be artificially enforced, not naturally grown. The process should be a collaboration between the mind of the author and reader, not a constriction.

Charles Dickens is a master of this. Without having to waste much time on character description at all, he selects the most recognisable and evocative of physical traits— an idiosyncrasy of expression, for example, or a peculiar habit— and allows the reader to build out the rest of the individual from that one vivid detail. Thus, no one person’s mental image of a Dickens character will be alike, and yet all have an effective sense of the personality they are conjuring.

At their very essence, words are limited. They are miniscule capsules of meaning, that can be fitted together like bricks into constructions that contain greater meaning still— and yet, paradoxically, their rigid, quantifiable structure relies on the free-flowing extrapolation and interpolation of the recipients’ imaginations to bring them to life. It is not the words themselves, but the space between the words, where the imagination is allowed to roam free, conjuring meaning in a manner that can only be understood as divine intervention. God, therefore, truly does live in space.

One might think this means the literary styles utilising the least number of words would be most effective at stimulating the imagination. After all, these would technically contain the most amount of blank space. And following this logic, the minimalism of Ernest Hemingway would paint far more illustrious mental pictures than Thomas Hardy’s verbose realism.

The answer, of course, will boil down to personal taste— I would simply like to remark that, perhaps counter-intuitively, the minimalist may require an even more judicious and considered control of their vocabulary than the less austere author does.

Too often, the label of minimalism has been employed simply to cover up bad writing, but the conscious and clinical choice to pick one word over another is very different than merely possessing a stunted lexicon. As restricted as a minimalist piece is, each word must carry the weight that entire paragraphs would in other genres, and therefore the author cannot afford to be lax with any semantic choice that they make. After all, more space between words doesn’t naturally promote more freedom of imagination in the reader— the language bordering those spaces must be fruitful enough to provide healthy sustenance for the mind of the reader to nourish itself on. Poorly chosen words are poor nutrition for the mind, and the page will surely be left barren.

So, this judicious economy of language does not demand sparsity, but surety of words. As the minimalist writer can paint vivid mental pictures with few words, so too can the maximalist writer encourage imaginative exploration with less blank space around their verbose descriptions. A prominent example of this that springs to my mind is from Thomas Hardy’s The Return of the Native. The book is set primarily upon the rolling hills of Egdon Heath, a fictional stretch of countryside that Hardy spends no less than four pages (of my edition) describing. Hardy casts his authorial eye across many aspects of that ‘Titanic’ landscape as the sky overhead darkens to twilight, the shadows lengthen behind the trees and scrubs, and gloom gathers in the pits of the earth. To the Raymond Carver enthusiast, such decadence of description would surely produce nothing but nausea— to my own mind, it is an exceptionally vivid and evocative section that beautifully weaves the backdrop of the entire novel.

A key reason to why the description of Egdon Heath is so effective, and didn’t cause me to close Hardy’s novel before even setting eyes on the second chapter, is because it somehow doesn’t feel overblown. Each element of detail follows on naturally from before, organically weaving together into a mental landscape that seems both bursting with life, and yet suitably sparse before the events of the novel take place. Like with Hockney’s paintings, this is an empty scene waiting for the players to take their positions, and the brief moment of silence beforehand allows the imagination to launch itself skyward.

Overall, regardless of the genre, the greatest literary description is able to nurture the imagination into action without doing the work for it. Instead of suffocating the agency of the reader with unnecessary and arbitrary word-jungles, each semantic choice must exist not merely to effectively convey its own meaning, but to allow the mind of the reader to fill in the gaps themselves. Too much blank space, and the writer has not used the full extent of their language to capture the reader’s attention— their pallet is colourless and uninspiring, their execution prosaic and lifeless. Too little space and there is not enough room amidst the clutter for the imagination to make itself at home.

The process of distilling thought into words is one of reduction, a sacrificing of the eternity of creative but unfocused potential to achieve clarity of communication. Therefore, it makes sense that the divine can be found in the space where words step aside, and allow the imagination to take over once more.

Thank you for reading,

The Watchful Scribe