Hello readers,

In case any of you haven’t realised, I regret to be the one to inform you that it is, in fact, January. I challenge anyone to not have their enthusiasm for life even slightly altered by this most dismal of months— the air is frozen, the sky dark and close, and though the days are short the weeks drag on and on into perpetuity.

If it is true that the human brain needs suitable daylight to awaken itself for the day ahead, then it could go a little way towards explaining why it is so difficult to engage oneself properly with work, when looking outside one’s window at any time except midday gives the sense of living in a cave.

It is vital, then, that during this period we all hold in our minds Percy Shelley’s most invigorating of lines: ‘If Winter comes, can Spring be far behind?’. Unfortunately though, whilst in the midst of this month, one can feel very far from Shelley’s portrait of his beautiful, redeeming Spirit of inspiration— and far closer to Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s vision of the unending ‘snowy clifts’ whose ‘dismal sheen’ drive the Ancient Mariner and his crew to a restless mania.

‘The Ice was here, the Ice was there/The Ice was all around’ indeed, and one cannot help but feel Coleridge’s painting of the South Pole is a pinnacle of the Romantics’ effort to correlate the external landscape of nature to the internal state of the human mind. Coleridge’s poem is one of spiritual stagnation and a Satan-like turning towards darkness of Miltonic proportions. The unending, unchanging ice floats that surround the mariner’s ship both exemplify and enforce that feeling.

This is at stark contrast to the manner at which the Mariner’s ship sets off on its voyage— his ship was ‘cheer’d’ as ‘Merrily did we drop’ into the water, the Sun shining ‘bright’ as it rises from the Sea on the left and drops again on the right. But these most favourable of conditions does not last long, for soon ‘A Wind and Tempest strong’ plays them ‘freaks’ ‘For days and weeks’. We can all empathise with this experience— I’m sure everyone has set off on some grand plan or project, bursting with optimism and energy, before the first signs of setback throw all into disarray.

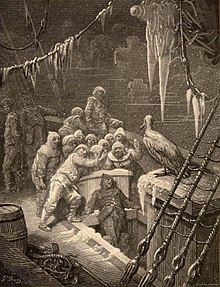

But the sudden storms do not lead to total wreckage, doom, or destruction. Instead, they leave the Mariner and his crew with something worse— stasis. The ship is blown deep into the icy waters of the South Pole, where no ‘shapes of men ne beasts’ can be seen amidst the ‘Ice mast[s]’ that float drearily by, ‘As green as Emerauld’. Though the ship does sail onwards, the blank, unchanging state of the surroundings evokes the feeling that no progress is being made at all. That is, until the appearance of the ‘Albatross’ that brings the ‘good south wind’— but it is common knowledge how that particular companionship ends.

For a much more comprehensive dive into the significance of the Albatross, the potential motivation behind its killing, and an explanation of the natural upheaval that follows, I would direct you to my essay ‘Who art thou that disputest with God’. As of now, I’d like to continue the present train of thought by considering the most famous passage from Coleridge’s infamous poem, and relating it to a modern experience of ennui. Ennui is a term that is almost parodied in its application these days— Google’s definition is ‘a feeling of listlessness and dissatisfaction arising from a lack of occupation or excitement’, and whilst it treads a line near to angst-ridden overindulgence and self-pity, it is also true that the human mind needs external feedback and stimulation to feel satisfied. When we do not receive a suitable sense of forward progression, we can be left feeling similarly stranded in a frozen, featureless landscape.

‘As idle as a painted Ship/Upon a painted Ocean’ is one of the most vividly crafted lines in all of poetry, and it perfectly captures how, once the Albatross has been slain (which was, arguably, the one source of higher Inspiration that the crew had to spur them onwards) the Mariner’s vessel becomes entirely still. Not a single external force appears to push it further on its way— and the outside influences that do appear are certainly not intent on coming to their aid.

But before those malign malefactors can make their appearance (which is when things really take a bizarre turn for the worse) Coleridge writes in evocative detail about the physical toll that immuration within the southern wastes has on the shipmen. Their water supplies exhausted, ‘every tongue thro’ utter drouth/Was wither’d at the root’, meaning that they could not speak as if they’d ‘been choked with soot’. In the day they are plagued by the sights of ‘slimly things’ that ‘crawl with legs/Upon the slimy Sea’, and at night they are tormented by the ‘Death-fires’ that dance in the darkness and make the water burn ‘green and blue and white’. Madness ensues, driven largely by the fact that, despite their dehydration, they are surrounded by water:

‘Water, water every where/And all the boards did shrink;/Water, water every where,/Ne any drop to drink’.

Now, if you would permit me, I am going to make a slight fanciful leap. For, whilst I myself have been mired in the motivational doldrums of January, I have found great significance in these lines (regardless of the fact that, spending my time as I do in a heated house in 21st Century England, my literal experience could not be further from the Mariner’s). After all, the bold venture we take annually into the new year is a little like an expedition in itself— one that, in the final hours of December, is certainly embarked upon ‘Merrily’ and with much cheering. The result of that merriment the next morning can indeed feel as if one is being assaulted by ‘Storm and Wind’, but it is not long after that when life settles down, and we find ourselves in the dreaded long, slow crawl back towards Spring.

Everywhere, all is encased in ice, and the greyness of our surroundings makes it far more difficult to inject colour into the things we need to do. And yet, in this day and age, we have colour and stimulation on hand, available at the motion of a finger. In theory, we can escape the stagnation of our frozen surroundings by jetting off to sunnier climes with the touch of a screen— or we can search for new avenues of thought and discussion in mere seconds.

There are multiple lifetimes worth of content to be consumed at our leisure, but such a wealth of choice not only doesn’t inspire us, it seems to distract and delay. The water that should allay our dehydration is everywhere, but it is actually a poison, not a cure. We are like the tragedy of Lord Byron at the end of his life— he travels on a mission of heroic intent to Greece, the very birthplace of Western myth, and though he implores the ‘Glory’ of that steeped history and heritage to break through his malaise and incite his ‘spirit’ to ‘Awake!’, his heart remains somehow ‘unmoved’.

So, what is one to do when trapped in this modern iteration of Coleridge’s icy waste? It seems we need an Albatross of our own to bring the encouraging south winds of change. Then again, can we trust ourselves to be any more open to such an intervention than the Mariner (and his crossbow) turned out to be?

In the end, after the Albatross had been shot, it was an act of humility that saved the Mariner from suffering the same hellish fate as his crew. Whereas before he spurned and scorned the wasteland surrounding him, refusing with a murderous hand that he was merely a small part of the grander order, he eventually is so worn down that he realises he is simply happy to be alive. What’s more, he grows to love the ‘water-snakes’ that move in a ‘flash of golden fire’ through the shadowy water as ‘happy living things!’ as well. He blesses them in an act that is entirely selfless; Coleridge emphasises that he was ‘unaware’ that doing so would save him from this purgatory of ice and death.

Therefore, if we are to seek out some useful wisdom from Coleridge’s most haunting of visions, perhaps it is the necessity of acceptance. One can either struggle against the natural order of things, or grow to love it— either turn away from the facts of the world (or even, towards it with a vengeful weapon) or find a way towards that same ‘spring of love’ that ‘gusht’ from the Mariner’s heart. After all, the embattled seaman somehow managed to find ‘beauty’ even in the slimy water-snakes of the Antarctic. Our own striving to become lost in an appreciation of our surroundings may mean that our ship finds its destination before we’ve even realised it moved.

Thank you for reading,

The Watchful Scribe

Poems Referenced:

–

‘Ode to the West Wind’ (1820), Percy Bysshe

Shelley.

–

‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere’ (1798), Samuel

Taylor Coleridge.

–

‘On This Day I Complete My Thirty-Sixth Year’ (1823),

Lord Byron.