If one were to try and define true wisdom, they would not struggle to find potential answers offered by all forms of thought and philosophy from all corners of the globe. Here, I ponder the differences but also the overlaps between Western and Eastern answers for this most paramount of questions, and also the transcendental, unifying truths that underly all great works of literature, no matter which culture or race they spring from. Ultimately, I believe that such a search would take us to the very core of civilisation- that is, the root of human narrative.

Hello readers,

I was recently speaking to a work colleague from Sri Lanka about his Buddhist faith, and he asked me what I thought the difference was between knowledge and wisdom. Our conversation was interrupted at this moment (unfortunately, we are not paid to wax philosophical for hours on end) and a little time passed, during which I came to the conclusion that knowledge is the domain of things that are known (extraordinarily perceptive, I know) and therefore can simply be committed to memory without much deeper thought, whereas wisdom is the ability to ponder things that we do not yet know, and also consider things that we know already in new, unfamiliar ways. Not the most erudite or competent of theories, I am aware, but it was the best I could come up with at the time.

When we next found time to speak, he listened to my definition and then gave me his own. While he was doing so, I found it fascinating just to what extent our respective Western and Eastern traditions have influenced our understandings of the world around us, and also to notice the overlap between these seemingly isolated philosophies as well. He told me that, according to Buddhist teachings, knowledge is based merely on information gleaned by our senses about the external world around us, whereas true wisdom is a perception of the inner reality within us, that requires more than mere sensory stimulation to connect with. In other words, wisdom is the ability to acknowledge things as they truly are, not just as they appear to be.

Now, immediately, this brought to my Western mind such notions as Plato’s Theory of Forms, or Kant’s idea of the noumenal world. It also provoked raised my hackles somewhat; by suggesting that to focus merely on the rational and the tangible was to lack in true wisdom, he seemed to be heavily insinuating that the secular West could never understand the ultimate truth of things in the way that other, more spiritually-inclined societies are able to. A voice of protest rose up inside me, inwardly shouting ‘Had the West not during the Enlightenment era foregone the abstract, immaterial ‘wisdom’ of spirituality, and focused solely on the rational, empirical world of things-as-they-are, then we would still be trapped in the archaic, undeveloped, pre-industrial civilisation of the time before modern science, and have not achieved any of the prosperities of industry, technology, and society that we take for granted today. And which, might I add, allow for the luxury of entertaining such abstract lines of thought.’ Which of these arguments has more truth in them, or whether there is a more nuanced answer in the centre of this dialectic (which I suspect there is) would be for another post, or perhaps another website entirely, to explore.

But beyond this first reaction, I began to wonder how this concept of wisdom as opposed to knowledge could relate to literature. I have always believed that reading widely, and studying the humanities as a whole, is the best way to gain a truly rich, varied and comprehensive understanding of the human condition (which is, as it happens, something that can never be fully grasped, for it is not quantifiable like the object of scientific study). Challenging literature, filled with sophisticated and complex characters and interactions, has the power to completely change how one views the world after the last page is turned, as well as how we subsequently go about interacting with the people in our lives. Whereas once the mind of another can seem alien, shrouded in shadows, reading about many different fictional personalities can in turn allow us to lift those obscuring clouds by strengthening our powers of empathy and familiarising ourselves with how human beings act around one another.

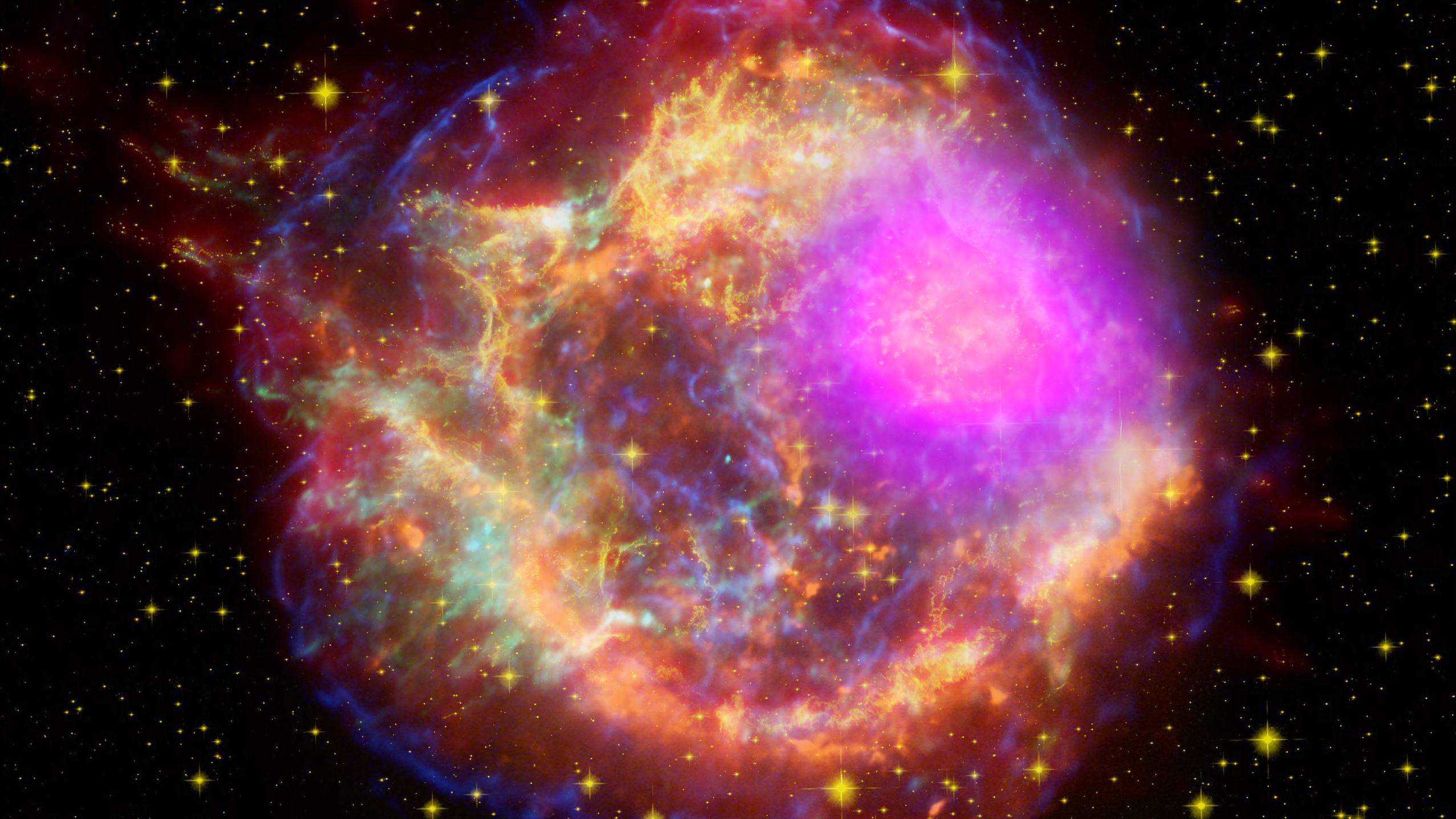

There is an analogy that comes to my mind, regarding how the study of the humanities lends a different kind of knowledge about our species than more scientific disciplines like biology or psychology. (This is not to disparage those areas, of course— they are far more profitable studies than my own, and equally as interesting.) Imagine a person who studies the science behind a supernova. They dedicate their life to measuring the chemical reactions, the physical processes, and the resulting cosmological disturbances that occur as these extraordinary, sublime acts of natural majesty take place. Now, imagine another person, who spends their time not studying the theory of the supernova, but simply watching them occur. They watch hundreds of the explosions take place a year, revelling in their splendour, and also gradually noticing the similarities and differences between each event. They become so familiar with the processes of each supernova, and yet constantly surprised by their unique characteristics as well. Who of these two people understands more about supernovas? Do either? Or both at the same time, in different ways?

The kind of comprehension-through-familiarity that reading gives about the human disposition is not one that would pass any scientific rigour, but seems similar to the concept of ‘wisdom’ that my Buddhist friend was explaining to me. There was something else that he told me about this characterisation of wisdom as well, that was equally thought-provoking. He told me that it resides in a realm beyond language, that limited, structured human concept so integral to communication, and therefore cannot be expressed, but only felt at a deeper level.

Again, my mind instantly was set ablaze. Last week, I wrote a scribbling about Beckett’s Waiting for Godot, in which the character Lucky (representing, I argue, the deeper, unstable, irrational core of the human condition that society keeps in check) gives an incoherent page-spanning speech about God and God-knows-what. Here, it seems that the true wisdom within Lucky’s monologue is not in the words he says (most are jumbled and unintelligible, some are completely made-up) but in that which is implied by it, or perhaps the implicit meaning that lurks between the words (‘for reasons unknown’).

Similarly, if we are to find this true wisdom within the study of literature, perhaps we must look beyond the mere words on the page, beyond individual books, even, and at the greater, transcendent, unspoken truths that overshadow them. I believe that this is precisely what such paradigmatic thinkers as Carl Jung and Joseph Campbell and Northrop Frye were all investigating, to great success— the archetypal narratives, the structures of understanding that underpin the literature that we create, and thus lie within the roots of how we as human beings comprehend the world around us. They are so fundamental, so inherent, that we do not even realise they are there— so universal, that they cannot be contained within the meagre vessels of mere language. And yet such thinkers as these spent their lives tracking them down and mapping them out, and explaining them as faithfully as they could with the limited semantic tools that we possess, and as such gained far greater ‘wisdom’ over the true human constitution than many others can ever claim to own.

It is a never-ending challenge, to better elucidate such overarching patterns within the narratives that have across the ages conceived our entire civilisations, but it is perhaps one of the most important things that we can do. After all, a strong understanding of these narratives might be the closest we can get to a close relationship with something truly transcendent, that overleaps cultural borders, and binds every single human being together. That would be as spectacular as a supernova, no?

Thank you for reading,

The Watchful Scribe