In these heated days of reactionism and political tribalism, I consider whether there is a more measured path to cooperation and communication that we all must take in order to, simply, calm down. Let us open our minds to all possibilities, instead of locking our doors and closing the blinds to shut out the sunlight.

Hello readers,

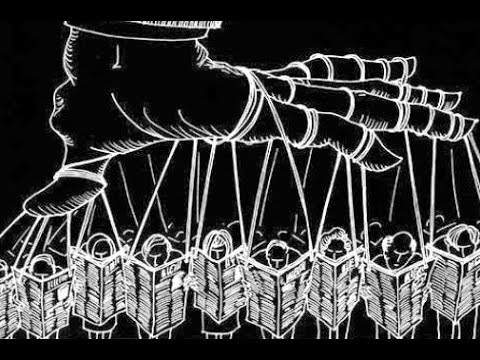

If there was one thing that I believed is the true root of many of our woes in modern society, it would be ideological factionalism. There is no single set of ideas, no political philosophy, no religion that can truly harbour all the answers to every problem (though many do claim to); this is partly because no serious problem can be tackled from one single angle, and must be tackled from all sides, overwhelmed by the collective power of many differentiated minds working as one. It is also because when a single dogmatic set of ideals is never challenged, and allowed to balloon into a stagnant and corrupt monolith, then it itself is perverted from a potential solution to a real problem as well. Usually, the more that an ideology claims itself to be the supreme and ubiquitous answer to everything, the more that it is more trouble than it’s worth— glance at the opposing and yet fundamentally familiar models of Fascism and Communism, those grotesque apparitions of the 20th Century, for example.

As such, there is a danger when a society finds itself split down ideological battle lines. Where once the common man ascribed themselves steadfast to a particular religion (which tended to be a result merely of their place of birth) for which they could very well be prepared to turn a blind eye to blatant humanitarian atrocities in the name of a ‘higher’ morality, it appears that in these secular days this role is being fulfilled by political tribes, the two ‘wings’ of a plane that has already caught fire, which is causing much the same result. In the name of loyalty to the reds, the blues, or the colours between, people are willing to disavow even their own family members in the name of their own, precious ideals— and as Orwell so brilliantly illustrated, the bond of the family unit is the final defence against the totalitarian grip of the encroaching state.

This, of course, is wrong, though it is far easier to lambast such failings in a website post than it is to resist the mind-numbing allure of blind obedience in the real world. The only thing that should elicit any sort of loyalty is good ideas. When the next election traipses down the road, and someone closes their ears to facts and blindly votes for a candidate just because their party is whom they have always allied themselves with, it is because they finding too much of their own identity within a pre-defined set of ideals— this is dangerous when the answers it supplies are finite, flawed and necessarily self-preserving, as all political wings are.

Unfortunately, there are countless scientific papers espousing that this desire to blindly follow an imperfect tribe is inherently and inescapably human. People are willing to pervert the very fabric of their perception of reality, just to sweep under the rug any facts that may prove subversive to their chosen party line.

What is instead required to fortify one’s own brain from the puppet-strings of political ideology is a willingness to think critically. To consider all arguments from all sources, no matter how alien or unfavourable they may seem, and to formulate an individual and fair consensus from that accumulation of ideas. Naturally, it is far harder to concentrate on conceiving of a unique version of an opinion, than it is to adopt one that has already been laid out nicely by someone (in some ways) far more intelligent than we— and yet complacency can kill, and lest we wish to tear each other apart in the name of flawed dogmas that we’ve scarcely even thought about, let alone fully understand, we must take the path more treacherous.

So, what could be a tonic to this ill-placed faith? Well, given the nature of the website, it won’t surprise anyone when I say that one potential way of both broadening the mind to more critical ways of thinking, and balustrading it against the pull of promises from Siren-like ideologies, is to read widely and well.

One of the fundamental differences between the scientific disciplines and the humanities is that one deals with concrete facts, and the other with theoretical hypothesis. Firstly, I will make it clear that this is not a value judgement— this difference is necessitated by category, for science is based in the material world (in which there are obviously truths and falsehoods) and the other in human thought (in which it all becomes more ambiguous). Secondly, I am clearly not saying that there is no room for hypothesis in science— indeed, the word itself seems only at home when ‘scientific’ is found preceding it. However, the scientific hypothesis is designed to find existing, irrefutable material fact from theory. It is true that findings presumed as factual by previous scientific studies are always capable of being found out as false by new developments in research, but that does not disprove the reality that there are material truths and laws in the natural world that are unshakable, however hard they are for our mere human minds to uncover.

A hypothesis in the humanities, however, is somewhat of a path without a destination, for there can never truly be hope for a definitive answer. Even in the study of history, which seems to deal in concrete fact, the interesting endeavours come when the historian tries to piece together which events precisely influenced the formation or failure of another, or what motivations key figures must have had in order to do the good or bad that they did— all of these secrets cannot be known, indeed some may have been unconscious even to the minds that were carrying them out, and thus ultimately history is a kind of a reverse science, with the origin being in fact and the endpoint being in hypothesis.

Regarding the study of literature, I have recently been considering the tired old witticism of the average schoolchild (something that I intend to write about in greater length) about an infamous set of blue curtains. Namely, that ‘just because the curtains are blue, it doesn’t mean that the writer intends them to be sad’.

Now, so pervasive is this challenge, and so convinced of its validity are many of the people that espouse it, that I believe the English subject should do much more to discredit it. Partly, this is because it is not very difficult to dismantle. After all, what the writer intends is completely irrelevant to the potential meaning within and interpretation of their work. If writing is like recorded dreaming, then it must surely follow that, as one does not ever truly understand the cognitive processes behind a dream, then there must also be an unconscious element to writing as well. As a writer of fiction, I personally can attest to this— it is a bizarre and thrilling experience to go back over work that I have penned in the past with the mind of a literary critic, and realise that there are connections and significances and thematic consistencies to be found in the writing that I myself had no idea were there as I was writing it. If one wishes to be convinced that they truly are not in control of their own mind, then this is an excellent means of proof.

Some people dismiss the humanities as dealing in trivialities and abstracts, believing that true value is found in uncovering truths that can be verified empirically. After all, one can only influence the material world for the better by dealing in the facts of that very material world. This is true, to an extent— though as is clear to anyone who’s ever engaged with a work of art and felt something because of it, or listened to music, or even anyone who’s paid any attention to their own thoughts, the human being is not a merely material entity. And it is precisely that openness to theory that gives the humanities its worth.

It is a cliché that there are no right or wrong answers in the study of literature, but once one accepts that the opinion of the author is irrelevant, then it becomes the core of the discipline. This lends a sort of intellectual democracy to the humanities— all potential arguments are valid, as long as the arguer has thought about it enough and has enough confidence to make a compelling case. Of course, the argument that has more supporting evidence in the text will be deemed better, and will convince more of its worth. But as there is no way of truly discerning what the correct answer is— what is Conrad’s ‘heart of darkness’, were the events of Macbeth the fault of the man or his wife (or both), what exactly happened at the chilling end of The Turn of the Screw— all opinions are open to consideration. With the hierarchy of facts dissolved, it depends simply on the wit and the courage of the thinker to offer new truths to the intellectual discourse.

It is also for this reason, that my biggest piece of advice for anyone writing a literature essay is to engage with an idea that you are passionate about exploring, rather than one that you think is already true, and therefore safe— attempts to pacify the tutor with arguments that they likely already agree with result in stale, boring rehashes of old tunes, and as long as they are a good tutor (one who is willing to have their own opinions challenged, for what else would be the reason to work in academia but that) then they will be far more excited by the risk of a unique and unfamiliar interpretation of a text. As far as I’m concerned, the more outlandish and less mainstream an argument, the better.

Oftentimes, a good sign of how revolutionary and important an argument is, is how much other people are whipped up into a frenzy trying to denounce it.

I will end by returning to the beginning. In a world of political factionalism and blind adherence, literature reminds us that there are no real answers when it comes to the actions of human beings, and thus there exists no be-all-end-all philosophy or ideology that can be left unchallenged. After all, we can only gaze at the pure truths of science through the capricious, obscuring prism of the human mind, which is a little like staring out at the world through a misted glass window. Even when we believe we have the truth, it is a view tainted by our own individual biases and preconceptions. History is a process of finding equilibrium through opposing forces— the more the pendulum swings cataclysmically to one side, the more you know that you are soon headed back down to the point of perfect balance. Similarly, we ourselves must endeavour to facilitate that aforementioned democracy of ideas in our own minds, for by shutting ourselves off to entire other ways of thinking simply due to our preconceived prejudices and presuppositions, we are leaving ourselves intellectually lopsided and prey to totalitarian exploitation. The more that someone claims they have the truth, the more one can be assured that they are blind.

Thank you for reading,

The Watchful Scribe