Hello readers,

I recently read, in the London Review of Books, a piece entitled ‘In Need of a New Myth’ by Eric Foner, considering the work ‘A Great Disorder’ by Richard Slotkin. Within the text in question, Foner writes, Slotkin strives to argue that the current societal rifts and tensions in America are stimulated not by ‘economic or political’ spurs, but are instead ‘essentially cultural’. Ultimately, Slotkin points accusatorily at the ‘lack of unifying national myths’ that can transcend state boundaries from the Atlantic to the Pacific and bind all under irrefutable ‘shared views of the country’s history and future’.

It feels needless to say that we in the West are having something of an identity crisis at this moment. As a growing tide of revisionist historians painstakingly unpick our myopic perceptions of national history, shedding long-obstructed sunlight upon underappreciated voices or crying aloud ‘Eureka!’ at the uncovering of today’s instance of social injustice, it feels that even the aspects of our heritage which don’t give us cause to wince in shame— or that, dare I say, we can be proud of— are being shredded apart in this gold-fever of retrospective retribution. On top of this, as we open our borders (with more or less welcoming arms, bad actors aside) to a broadening variety of outsiders, those who link their sense of national identity to purely aesthetic characteristics can feel that those intrinsic roots are under threat; of dilution, some ‘great replacement’, or otherwise.

No more so does this seem long-lastingly relevant than in the United States of America, that very (often self-proclaimed) bastion and bulwark of modern-times liberty and justice. Its maps appear blotched in stark, oppositional swathes of red and blue, and where they come into contact we see not purple, but the deep oranges of flame. Having read much recently of myth, symbolism and archetype, I would agree with Slotkin that the power of a unifying story is one that many may underestimate. Yet it is also true that, if we ourselves struggle to sustain a national identity in pin-prick Great Britain, this must be an endeavour near-impossible in the gargantuan landmass of our mutineer-turned-bosom buddy.

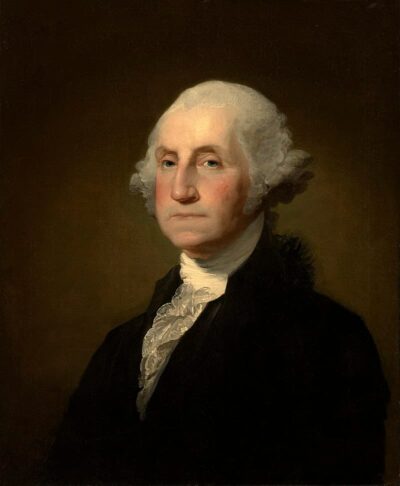

What is it, then, about the legacy of George Washington and the Founding Fathers that failed to bind together their brotherhood of man for even a century? After all, if we are searching to locate a national founding myth for America, this would surely be it (Slotkin views this ‘Myth of the Founders’ as amongst a series of others, including the ‘Myth of the Frontier’ and ‘Myth of Liberation’— but as we here are focusing on tales of origination, we shall consider merely the first). When Washington and his finely-coiffed fellows proclaimed a new constitution, they did so with voices that rang out across the ages. Yet increasingly, one feels that the resulting tremor from that immense sound have shaken and ruptured the very same foundation that it served to create.

To properly consider why America’s founding myth has faltered in maintaining a universality of common consensus, I’d like to consider perhaps the most infamous of founding myths, that of Romulus and Remus. As the story goes, when those wolf-suckled brothers decided to construct a great city along the River Tiber, they could not agree upon which hill to found it; a skirmish ensued, in which Romulus bashed out his brother’s brains with a large rock (or at least, that’s the version I recall). The myth also has the added garnish of detailing from where Rome got its nomenclature; apparently Romulus was assailed by no post-fratricidal remorse when considering if he should honour the name of his rudely-extinguished sibling.

Now, I am not at all trying to suggest that the Roman Republic and the far more expansive Empire after it was a uniquely harmonious or even contented group of peoples, all united together beneath the banner of a brief cautionary fable against the dangers of brotherly competition. Few civilisations have been as blood-soaked as Ancient Rome. But I would also hazard to argue that few civilisations have been so proud of their culture and heritage as the Romans (part of the reason as to why they were so insistent on forcing it onto everybody else). Conversely, as is the topic of this particular thesis, depending on where you are in the States, not so many may share the same unabashed pride of being an American. As it turns out, recent studies back me up in this assumption. I do not say this with glee, I must emphasise.

There are two main reasons as to why I feel that the founding myth of Rome managed to instil a core sense of unifying nationalism in its people more successfully than the tale of George Washington and co. seems to have. (Naturally, there are many more geo-political reasons to this variance of commonality as well, such as the close presence of dangerous enemies and a longer history, which Slotkin covers in his own work.)

The first of these reasons may seem somewhat reductive— perhaps even anticlimactic. But I believe the greater effectiveness of Rome’s founding myth (when held against our criterion) is that it, by and large, is not true.

Indeed, the moment that a founding myth crosses the threshold from fiction to fact, it does so from symbolic significance to scientific scrutiny; gone is its inherent power of abstract, idealised meaning, replaced by the tangible and the verifiable; obsessions about the characteristic integrity of the people involved, of the rationality of what was said and done, or the exact verisimilitude of the version of the account being told, right down to the dates at which it happened (1776 or 1619, to give an example).

Nobody debates to a serious degree whether Romulus was ‘morally justified’ in bludgeoning Remus, or whether they would have found more success in cooling off and chatting it out. That’s not the point of the myth; the symbology of the first act of Roman heritage being one of conquest and triumph sets the tone for the hawkish pride of its peoples. The simple brutality of the myth, easily comprehended by all ages, is what enhances its effectiveness. It is not muddied by questions of empirical authenticity or moral judgement, because neither of the brothers were real in the first place.

Compare this with the Founding Fathers. The effectiveness of their unifying legacy feels entirely tarnished by squabbles about their individual integrities, their behaviours, or even whether they really meant what they were saying at all. Exemplifying this yet further is the fact that this disparagement of their influence has come from both sides of the political spectrum (when it suits their preconceptions)— those driven to pick apart America as a nation of institutionalised oppression lambast its progenitors for being embodiments of that oppression, whilst Slotkin writes that the Confederate leaders declared Thomas Jefferson had ‘simply been wrong’ in his pronouncement that ‘All men are created equal’. That is quite the glaring error, if so.

We do not have this same problem with Romulus and Remus, for the focus is on what they did, not what they said. One can swap and substitute much of the wording in the myth without affecting its overall message (indeed, they don’t even need to say anything at all). On the other hand, even a very small alteration of the words spoken or written by the Founding Fathers can have devastating effects on their application; adding, for example, an innocuous ‘not’ to the aforementioned Jefferson quote.

Which, in turn, leads on to my second reason for the efficacy of Rome’s myth; the separation of the founding myth from the development of the constitution. Whether written or uncodified, constitutions have the impossible task of being both precise and universal, and as words are by nature imperfect vessels of meaning, the notion of the exact intention of their author will be quarrelled over. The issue with the American constitution being tied so closely with the real-life Founding Fathers is that any and every disagreement with the constitution is reflected onto the Fathers themselves. In turn, as the founding myth itself is embodied in the integrity of these individuals, each dispute over and discreditation of the constitution is another gradual discrediting of the myth as a whole.

Rome’s constitution, meanwhile, was a patchwork palimpsest of ideas and structures imposed and enforced by various historical figures, from the public tribune system of the Gracchi to Cicero’s artful Res Publica. It was flawed, often proven futile, and incessantly under fire. And yet, it left no mark on the power of the Romulus and Remus myth. Beyond the political and social upheaval that immiserated the lives of the normal Roman people from the first kings to the final Emperor, they could always contrast that strife against their mythological ideal of a strong, conquering nation state; an untarnished foundation, grounded in a specific yet universal figure of a different age, safe in the realm of symbolism, upon which to base their holistic sense of being one amongst many.

In his LRB article, Foner considers 20th century American historian Daniel Boorstin, who pointed to the ‘pragmatic temperament’ in his fellow countrymen that led them to ‘reject ideological debates, and get down to the business of scientific and economic advancement’. Boorstin was not coy about his approval for this push towards rationalism, though I would suggest that it reaches its limits when attempting to provide a myth that unites a vast group of people varied in perspective, geography, and upbringing. Pure empirical reality simply does not go far enough; a founding myth must tap into a psychology beyond reason, and appeal to the inherent inclination towards symbology and narrative that is truly universal amongst humans.

As a final note: this may play a part in explaining why, compared to other Western countries, Christianity is still most prominent in the United States. Their founding myth, too rooted in the mire of reality, fails to suitably provide a binding force, and so its people turn to another myth to ground themselves in instead. Come to think of it, Christianity is something else that’s at its worst when caught up in the minutiae of empirical evidence and historical proofs; it is at its most wonderful when it abandons futile and reductive truth claims and instead appeals to the universal, the symbolic, and the mythological.

Is there a remedy for this situation? I hope so; America’s own role as a symbol to the rest of the world is invaluable, especially when faced with such an uncertain future. As Lincoln said, though they may be ‘strained’, our ‘bonds of affection’ ‘must not break’; fabricated untruths can be (and usually are) wielded to divide and control, but perhaps we should consider how an application of symbology and storytelling could unite us as well.

Thank you for reading,

The Watchful Scribe