If there was an era in which it could be argued that the mind of the modern man was born, it would be the Enlightenment period. As Pagden writes, the era ‘[stood] for the claim that all individuals have the right to shape their own end for themselves rather than let others do it for them’,[1] and as philosophers like Voltaire denounced monoliths like Christianity as a ‘long-standing infection’ whose doctrine ruined the ‘true philosophy and culture’ of the Greco-Roman Empires,[2] there became a fundamental shift away from pre-existing dogmas that imposed their own ideologies onto the common man. However, almost twenty years before the Enlightenment swept across Western Europe, John Milton wrote ‘Of man’s first disobedience’[3] in his epic poem Paradise Lost. Notably, it was his characterisation of Satan, and his ambition to wrest agency from the dominion of God, who became a glorified symbol of individual liberty against oppressive institution for many thinkers during the Enlightenment and beyond; various reincarnations of the figure emerged in later works, such as the titular seaman in Coleridge’s ‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere’. However, after the initial ecstasy of such rebellion, one may find that being of the Devil’s party can bring more anguish than it does ascension.

Rejecting Divine Order

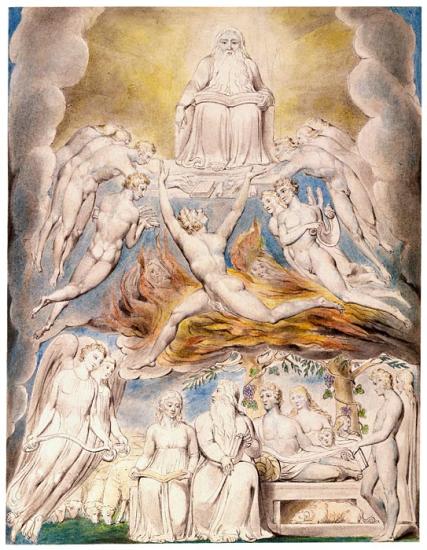

As Abdiel tells the rebellious angels in book V of Paradise Lost, it is the inherent purpose of the angels to ‘exalt/[Their] happy state under one head more near/United’ and exist in servitude to God. He reminds Satan that God ‘made/Thee what thou art’ (PL, 139), and Satan’s retort is to contend with the very notion that God is their creator at all, claiming that they are ‘self-begot, self-raised/By our own quickening power’ (PL, 139-140). As Frye writes, creation is the ‘basis for dependence, whereas autogeny is the basis for autonomy’;[4] in claiming independent inception, Satan is telling his rebel angels to ‘cast off [the] yoke’ of the very concept of a divine hierarchy with God as ruler, thereby forfeiting their existence’s singular purpose. Instead, Satan becomes their figurehead, promising them that their victory will achieve not ‘liberty alone […] but what we more affect/Honour, dominion, glory and renown.’ (PL, 154). And yet, as St Augustine wrote of the Biblical Lucifer’s choice, upon sundering himself from God, he ‘became less than he had been, because, in wishing to enjoy his own power rather than God’s, he wished to enjoy what was less’.[5] This is also the case for Milton’s depiction of Satan; Frye explains that ‘In the Christian conception […] evil is totally subordinate to God: it is good in its creative intention, but perverted from its normal goals’.[6]

When considering Milton’s hell, the ‘prepared ill mansion’ of the rebel angels (PL, 168), it seems an exact manifestation of Frye’s words. Hell is a place ‘As far removed from God and light of heaven/As from the centre thrice to the utmost pole’, a ‘dismal situation waste and wild’, devoid of the purpose that being within the hierarchical structure of Heaven provides. (PL, 5-6). Its ‘darkness visible’ is both a clear reminder that they have fallen far beyond the kingdom of God, but also that the only reality visible to them now is the formless void beyond His influence and direction. At the same time, in accordance with the component of Frye’s quote that calls evil a mimicry of good ‘in its creative intention’, we also see that this new domain provides Satan with a place to manifest exactly what he wants. Before the war of book VI, Abdiel tells Satan that, while the loyal angels ‘serve/In heaven God ever blessed’, Satan can ‘reign […] in hell thy kingdom’, in an infernal mockery of the divine monotheism (PL, 147). Indeed, rather than denounce his rhetoric for leading them into being ‘condemned/Forever now to have their lot in pain’, the rebel angels actually collect around Satan in fierce worship, with a ‘faithful[ness]’ that moves the author of evil to tears (PL, 24). As Beelzebub tells the divine enemy upon his awakening, simply hearing his voice will rouse ‘their liveliest pledge/Of hope in fears and dangers […] they will soon resume/New courage and revive’ (PL, 12). It is either that for the rebel angels, or admitting to their mistake and humbling themselves in forgiveness. Thus, with ‘Atlantean shoulders fit to bear/The weight of mightiest monarchs’, in providing the rebel angels with a new purpose to corrupt ‘By force or subtlety’ God’s new creation of man, Satan assumes the sole responsibility for their salvation, and becomes the individual bearer of their new meaning (PL, 40-41). He now ‘seemed/Alone the antagonist of heaven (PL, 44)’; but as Frye states, ‘Hell for him is existence as his own deity’, in both senses of the phrase.[7]

Like the grand designs of the rebel angels when declaring war on God, Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner and his fellow sailors share a jubilant purpose when they set off from the harbour. The tone of celebration and festivity surrounding the occasion is clear, as ‘The Ship was cheer’d, the Harbour clear’d’ and ‘Merrily did [they] drop’ into the sea.[8] However, as they sail further South, this resolve is tested by the endless ice and snow; like the ‘waste and wild’ expanse of Hell, these frozen seas are a formless, empty place, whose ‘dismal sheen’ of the ‘snowy clifts’ reflect the malcontent of the mariners (RAM, 148). It is fortunate, then, that the Albatross appears ‘Thorough the Fog’, whose appearance is, as Martin articulates, ‘more than a bird of good omen, [as] he brought immediate relief’.[9] Specifically, the Albatross’ relief comes in the form of a ‘good south wind’ that compels them on their course, a literal embodiment of the sublime purpose that the Albatross provides. Indeed, the sailors see the Albatross as if it ‘were a Christian Soul’, hailing it ‘in God’s name’, and its divine significance is only increased by the fact that the bird appears unfailingly ‘for vespers nine’. As such, within the meaningless wastes of ice, the sailor’s main source of comforting purpose becomes entertaining the company of the Albatross who comes ‘every day for food or play’.

Which is why, perhaps, the Ancient Mariner struggles to admit that ‘I shot the Albatross’ and hurries on past the dreadful crime without providing any explanation for his actions (PL, 149). With Paradise Lost in mind, there seems a parallel between the coronation of the Son, and Satan’s resulting envy, and the adoration of the Albatross, and the mariner’s resulting wrath. Much as Satan believed the ascension of the Messiah to be an ‘abuse/Of those imperial titles which assert/Our being ordained to govern, not to serve’ (PL, 138), the shooting of the Albatross seems a revolt against the divine purpose it bestows upon the rest of the crew. Perhaps witnessing them find meaning not in the rational, secular needs of the expedition, but in the hopeful prospect of divine providence, threatened the mariner’s chosen system of value; rather than reconfigure that understanding and ‘bend/ The supple knee’ (PL, 138), he believed his own reason to be superior, and removed the thing that challenged it. Indeed, for some it is ‘Better to reign in hell’, where one’s fragile perception of truth is safe, than ‘serve in heaven’, whose meaning is beyond their comprehension (PL, 11). Following this, the rest of the sailors first ‘cry out against’ him ‘for killing the bird of good luck’, but soon they too denounce the Albatross as the ‘Bird/That brought the fog and mist’ and agree that its murder ‘’Twas right’. In the prose glosses of the revised 1834 edition, Coleridge makes it clear that this makes the sailors ‘accomplices in the crime’, similar to how the rebel angels’ desire for vengeance through Satan only worsens their original sin. And yet, the mariners’ actions are also understandable; reduced once more to the aimless, frozen wasteland, they would gladly accept any purpose for their futile expedition, as malicious as its bearer may be. Thus, they hang the Albatross around the Mariner’s neck ‘Instead of the Cross’, as a desperate, visual proclamation that they are renouncing divine purpose, and uniting under the Mariner’s crime instead (RAM, 150, 170, 151).

Consequences of Claiming Autonomy

By assuming the shared purpose of corrupting Adam and Eve, Satan becomes the sole hope for them to rise once more into God’s light, and as such establishes himself once more as the single site of meaning for the rebel angels. Yet, as C.S. Lewis attests, the irony here is that the ‘door out of Hell is firmly locked, by the devils themselves, on the inside’ due to their refusal to repent; when Mammon and Satan decide immediately that seeking forgiveness is not an option, their whole debate becomes ‘an attempt to find some other door than the only door that exists’.[10] Furthermore, it is clear that, despite their lofty claims of independence, they go to every effort in recreating whatever pastiche of God’s divine structure they can. The rebel angels construct Pandaemonium, ‘the high capital/Of Satan and his peers’ in likeness of the kingdom of Heaven— but in order to fit inside for the assembly, they must ‘Reduc[e]’ their ‘incorporeal spirits to smallest forms’, a physical sacrifice of one’s own being in the name of individual agency (PL, 29). When they praise Satan for his promises of salvation, they ‘as a god/Extol him equal to the highest in heaven’, despite being trapped in the very lowest bowels of creation (PL, 44). Whereas under God’s reign ‘His laws our laws, all honour to him done/Returns our own’, the other rebel angels are quite literally left behind while Satan pursues their purpose on his own; they can only pass the time in disparate loneliness, by ‘wandering, each his several way […] as inclination or sad choice/Leads him perplexed […] till this great chief return’. Their minds are filled with ‘thoughts more elevate […] Of providence, foreknowledge, will and fate’, as they try to access in the mind what they once had in every aspect of their being, yet they find themselves in ‘wandering mazes lost’ (PL, 139, 45-6).

Perhaps the cruellest irony of all is that the being on which their hopes rest is no less miserable: in his soliloquy in book IV, he proclaims to the sight of God’s ‘surpassing glory crowned’ that he ‘hate thy beams/That bring to my remembrance from what state I fell’ (PL, 85). Forsyth writes that here, Satan ‘recognises that it was Pride and worse Ambition that threw him down, that he had no good reason to rebel’ and ‘that he fell of his own free will’.[11] This, then, is what Milton means when he writes of the ‘apostate angel, though in pain/Vaunting aloud’ (PL, 7). With Satan’s every pretension of confidence in his actions, the peril of their impending ‘Disdain’ upon their realisation of his hollow words grows, thus always promising ‘in the lowest deep a lower deep/Still threatening to devour me’ (PL, 86-7). The ‘lower deep’ he fears is not a material place, but a state of being in which he fails, the rebel angels turn their backs on him, and Satan loses the one thing that he covets above all else, his self-deification. Even more pertinently, if the rebel angels were to become disenfranchised from Satan now, then they would lose their last remaining system of purpose, meaning, and understanding right and wrong, however flawed it may be. This is reminiscent of Poole’s description of Chaos, a truly ‘Disconcertin[g]’ being that ‘doesn’t care about issues of ‘good’ versus ‘evil’’, as it existed long before them, and thus is the one thing that truly resides beyond God’s reign.[12] Even so, Forsyth articulates that ‘The ability to control Chaos is a primary source of God’s power’, and one only held by Him.[13] Therefore, falling into Chaos would place the rebel angels more at the mercy of God than ever before, with no kingdom for Satan to rule, and no way of escape except for God to bestow His order unto them. But before this can occur, in Book 10, after Satan successfully tempts Eve to eat the apple and he returns to Hell victorious, the rebel angels discover that they never truly escaped their position as subordinates to God at all, and find themselves shackled back into the very divine order that they revolted against; an ‘annual humbling’ of ‘certain numbered days’ sees them turned into serpents, the same form in which Satan tempted Eve, and forced to reach for ‘fruitage fair to sight’, whose transformation into ash upon consumption represents the empty promises and purpose that Satan provided them with (PL, 256-7). Crucially, this humiliation happens just as Satan is addressing his followers in triumph, so that instead of exalting in the new purpose that Satan has successfully won, all they can hear is the ‘dismal universal hiss’ of serpents, befitting the ‘dismal situation waste and wild’ that they are imprisoned inescapably within (PL, 255, 5). In Milton’s words, a ‘greater power/Now ruled [them]’; if they are to deny their first purpose of existence, another, far more pernicious one shall be thrust upon them instead.

Upon the killing of ‘the Bird/That made the Breeze to blow’, and the Satanic rejection of the divine purpose it bestowed, the mariners’ ship becomes ‘stuck […] As idle as a painted Ship/Upon a painting Ocean’. No wind, no driving purpose appears to guide them on their way, and they find themselves immured in doldrums of meaninglessness. Their one solace is to ‘speak only to break/The silence of the Sea’, but even this one last respite is stolen from them, when ‘thro’ utter drouth’ their tongues become ‘wither’d at the root’, like the ash that the apples of hell turn to in Satan’s mouth. (RAM, 150-1). Thus, the crew are rendered unable to manifest their blasphemous thoughts in free expression, like Satan and his followers after they are transformed into snakes. Indeed, it is significant that in order to point out the appearance of a sail on the horizon, the Mariner ‘bit [his] arm and suck’d the blood’, described in the glosses as a ‘dear ransom’; to derive meaning from within the individual, rather than the transcendent, requires a physical sacrifice of the body, reminiscent of the rebel angels reducing their ‘incorporeal spirits’ to partake in Pandaemonium (RAM, 151, 172). However, like in Paradise Lost, merely rejecting the divine order does not mean that you are freed of it, and if you do not submit voluntarily, you will be subordinated against your will. Once Life-in-Death wins the Mariner’s soul, a new ‘gust of wind’ starts up that ‘whistled thro’ the ‘hole of [the] mouth’ of her skeletal ship (RAM, 153); while the Mariner cannot speak his purpose into existence, this sinister force very much can. Similarly, Jones emphasises how the next time the Mariner’s ship moves, it is not guided by his own hand in partnership with the wind, but ‘numen-propelled’ at the mercy of Coleridge’s ‘lonesome spirit’ who seeks revenge for the death of the Albatross (RAM, 179). However, Jones also speaks of the ‘hierarchy of being’ that places the seraph above the numen living in the land of ice and snow, which allows them to take control of the vessel from the avenging spirit and guide it back to shore;[14] Jones’ conception of this ‘hierarchy’ can be extended to encompass not just the immaterial beings, but the human Mariner as well, and explains the reason as to why the angels reanimate the bodies of the sailors to save him from perishing at sea.

For, though the Mariner’s envious sin and stubborn folly has been very similar to that of Milton’s Satan thus far, there is a pivotal turning point that speaks of how the Mariner actually reintegrates himself back into God’s divine machination by accepting penance, the one redeeming action that the rebel angels could not do. In Paradise Lost’s book V, Raphael explains to Adam that whereas the reason of the angels is ‘intuitive’, the humans possess ‘discursive’ reason. In his footnotes to the poem, Fowler paraphrases Thomas Aquinas in explaining that this means angels ‘had perfect knowledge without discourse’; they need not turn to anyone else except God to provide themselves with purpose.[15] However, upon falling, this intuitive reason seems to be damaged, meaning that Satan’s followers now bicker and squabble amongst themselves in absence of a defining purpose. More vitally, their lingering self-perception of this flawless intuition, which they cannot admit to themselves has been corrupted, means that their reason cannot help but work to justify their mistake; when Satan sees the innocent beauty of Adam and Eve, he does not perceive it as something to be preserved, but as something that also deserves to be corrupted and delivered the same ‘woe/More woe’ as he, whom was once also so beautiful, now suffers (PL, 95). Conversely, when the Mariner sees the beauty of the water snakes, eve at the depths of his woe ‘A spring of love gusht from [his] heart’ and he ‘bless’d them unaware’ (RAM, 155). Martin stresses the importance of this being ‘unaware’: born from genuine feeling, not calculated duplicity.[16] Consequently, the Mariner’s curse is washed away by the rain, and he is able to speak once more. But instead of spreading blasphemy, his purpose is now to achieve penance by spreading the divine message that ‘He prayeth well who loveth well/Both man and bird and beast’ (RAM, 166). Like Satan’s ‘solitary flight’, the Mariner states that ‘The wind […] On me alone it blew’ (PL, 48; RAM, 163). However, when the Pilot’s boy sees the Mariner take the oars of their boat, he laughs that ‘The devil knows how to row’; the Mariner is one who fell in Satanic pride, but relinquished his sin and returned to the divine machination, thus escaping the doldrums of meaninglessness and regaining his driving purpose once more.

Finding (or Failing) Salvation

At the end of his tale, there is an intriguing admission from the Ancient Mariner, that ‘at an uncertain hour […] That anguish comes and makes me tell/My ghastly aventure’. Furthermore, when the wedding-guest agrees to hear his tale, it is not the Mariner’s rambling words of ‘a Ship’ that ensnare him, but the power of his ‘glittering eye’. When the wedding-guest wakes up the next morning, he does so a ‘sadder and a wiser man’, but there is an implication that the Mariner’s account did not quite manage to translate the arresting power of his gaze into a comprehensive, spoken narrative. (RAM, 166, 147, 167). Thus, the final message of Coleridge, and also Milton, is that only God can instil true purpose both into one’s own heart, and the hearts of others. Only God can create Order from Chaos. For all his glozing and shows of strength, inside Satan could not convince himself that he did not ‘pine […] His loss’ of ‘Virtue in her shape how lovely’ (PL, 109). The Mariner, moreover, whilst successfully arresting the wedding-guest’s attention for so long, is not able to fully convey the awful events that he bore witness to. Milton and Coleridge write that if one does not align their own inadequate reason with that of the infallible, undeniable truth of God’s word, they will be ruled by misunderstanding and deceit; as Frye states, evil is in itself ‘a lie, carrying at the core of its existence a falsification of its own nature’.[17] And if one does not bow to God’s ordained purpose, then they will be trapped in the Satanic, solitary flight through the domain of ‘eldest Night/And Chaos’; they may sometimes feel ‘glad that now [their] sea should find a shore’, but unlike the ‘dream of joy’ that the Mariner felt when he saw his homeland on the horizon, these shores only promise more misery, more Chaos, a ‘lower deep […] To which the hell I suffer seems a heaven’ (PL, 56, 59, 86).

Bibliography

Arkush, Allan, ‘Voltaire on Judaism and Christianity’, AJS Review, 18:2 (1993).

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, introduced by David Jones (London: Enitharmon Press, 2005).

Earlier Writings, trans. Burleigh (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1953)

Forsyth, Neil, The Satanic Epic (Princeton University Press, 2003).

Frye, Roland, God, Man and Satan (Princeton University Press, 1972).

Lewis, C.S., A Preface to Paradise Lost (Oxford: OUP, 1942).

Martin, Bernard, The Ancient Mariner and the Authentic Narrative (London: Heinemann, 1949).

Milton, John, Paradise Lost, ed. Orgel and Goldberg (Oxford: OUP, 2008).

Milton, John, Paradise Lost, Vol.2, ed. Alastair Fowler (Pearson, 2007).

Pagden, Anthony, The Enlightenment: And Why It Still Matters (Oxford: OUP, 2015).

Poole, William, Milton and the Idea of the Fall (Cambridge: CUP, 2005).

Samuel Taylor Coleridge: The Complete Poems, ed. William Keach (Penguin, 1997).

[1] Anthony Pagden, The Enlightenment: And Why It Still Matters (Oxford: OUP, 2015), p.vii.

[2] Allan Arkush, ‘Voltaire on Judaism and Christianity’, AJS Review, 18:2 (1993).

[3] John Milton, Paradise Lost, ed. Orgel and Goldberg (Oxford: OUP, 2008), p.3 (hereafter parenthesised as (PL, p)).

[4] Roland Frye, God, Man and Satan (Princeton University Press, 1972), p.28.

[5] Earlier Writings, trans. Burleigh (Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1953), p.237, quoted in Frye, p.23-4.

[6] Frye, p.22.

[7] Frye, p.24.

[8] Samuel Taylor Coleridge: The Complete Poems, ed. William Keach (Penguin, 1997), p148 (hereby parenthesised as (RAM, p)).

[9] Bernard Martin, The Ancient Mariner and the Authentic Narrative (London: Heinemann, 1949), p.19.

[10] C.S. Lewis, A Preface to Paradise Lost (Oxford: OUP, 1942), p.102.

[11] Neil Forsyth, The Satanic Epic (Princeton University Press, 2003), p.148.

[12] William Poole, Milton and the Idea of the Fall (Cambridge: CUP, 2005), p.157.

[13] Forsyth, p.116.

[14] Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, introduced by David Jones (London: Enitharmon Press, 2005), p.27 and p.19.

[15] John Milton, Paradise Lost, Vol.2, ed. Alastair Fowler (Pearson, 2007), p.312.

[16] Martin, p.9.

[17] Frye, p.23.

One thought on “‘Who art thou that disputest with God’: The Satanic Pursuit of Purpose in ‘Paradise Lost’ and ‘The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere’”

Hi, this is a comment.

To get started with moderating, editing, and deleting comments, please visit the Comments screen in the dashboard.

Commenter avatars come from Gravatar.